The

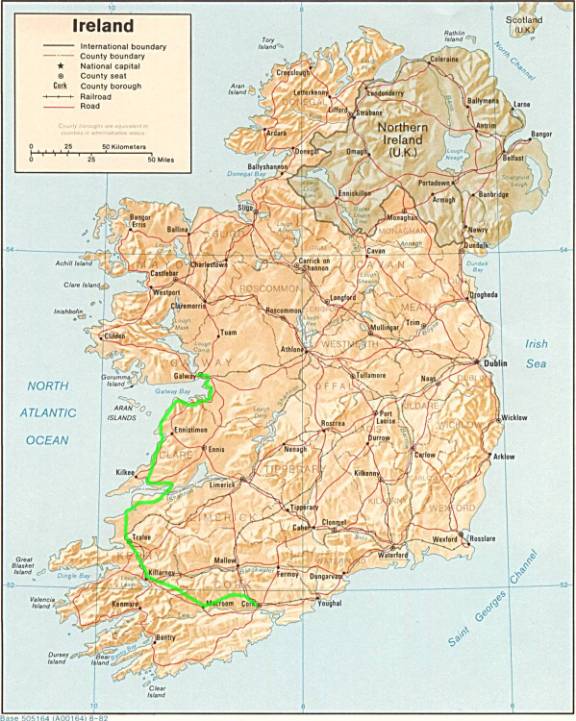

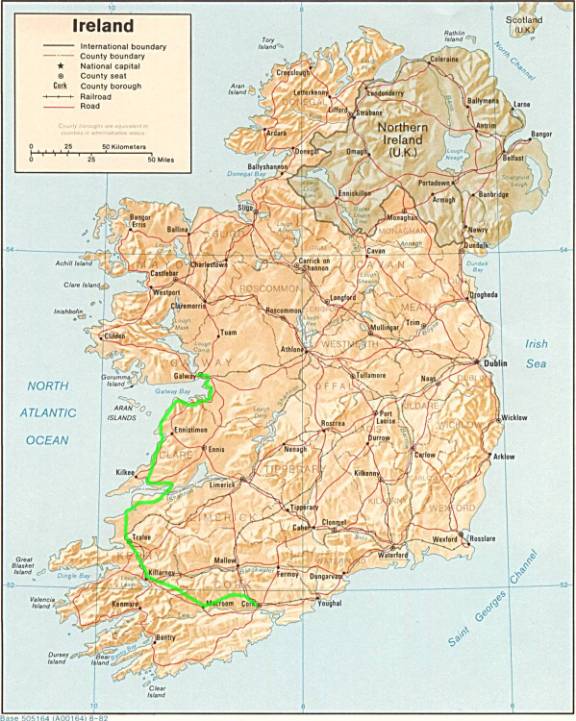

green line shows our approximate itinerary for the 7-day, 250-mile bike trip.

Biking in Europe had always been a childhood dream, and only at an older

age have I been able to live this dream. It

takes time, money, and planning, but most of all, it just means making the

decision. As Nike advertises –

“Just do it.” In the two

previous years I had biked in eastern England and in the Netherlands and

Belgium. This year I had a July meeting in Dublin for my first visit

to Ireland, and I decided a year in advance that I would bike somewhere in that

country in 2001.

The

previous year when I had returned from a bike trip through Holland and Belgium

to join a professional meeting in Amsterdam, the leader of that meeting, Len

Kleinrock, had said that he’d like to join me the following year for Ireland.

He wasn’t a biker, and I had doubts at the time whether or not he was

serious, but I welcomed his interest. He

is someone whom I have known professionally and personally for many years.

He teaches at UCLA, has written some well-known textbooks, and is one of

the four people credited with the invention of the Internet – for which he has

received numerous prestigious awards. One

thing that we have in common is that each of us has been a recipient of the

International Marconi Prize.

Soon

after, Len’s wife, Stella, bought him an expensive bike, and he began to cycle

near his home in Los Angeles. As

time went by, we corresponded regularly via email in planning to trip to come.

I decided that the best part of Ireland, the part where most tourists

went, was the southwest, and I laid out an itinerary with the help of the

Michelin and Ordnance Survey “Holiday” maps.

In laying out the trip I kept the trips relatively shorter than in

previous trips -- about 35 miles a day, as opposed to 43 – partly because of

Len’s inexperience, and partly to give more of an opportunity for sightseeing.

Little did I know at the time that Len would do better than I on the

hills that were to come in that innocuous-looking itinerary!

Having

decided on the region and the length of segments, the rest of the itinerary was

determined by the logistics. I had

learned the previous year in Holland that biking constantly into a headwind is

not fun, so this year I checked the prevailing winds for Ireland, which are from

the southwest, and consequently planned a northward journey.

The

decision on whether to rent bikes or bring our own was a pivotal one.

Previously I had always taken my bike with me on the plane.

It’s always nice to have your own familiar bike in a foreign country,

but sometimes the logistics are formidable.

In Ireland there is a special incentive to rent, because it seems to be

the only country where there is a rental system in which it is possible to rent

in one city and drop off in another. Given

that incentive, together with the difficulty in transporting my own bike from

Dublin Airport to Dublin for a meeting, and then to the southwest, and then

back, I decided reluctantly to rent bikes.

That decided, there were only a few cities where such rental and return

was possible. Going from south to

north in western Ireland, the choice was made for me – we would rent in Cork

and return in Galway.

Len

and I agreed on 7 days of biking, which was a compromise based on other

constraints that each of us had. I

picked the nightly stopping points at about the right distances along the route,

which starting from Cork were Macroom, Killarney, Tralee, Ballybunion, Milltown-Malbay,

Ballyvaughan, and Galway. These

were the towns along the way most favored by tourists, but in truth they were

about the only towns along the route where you could easily make reservations

from abroad. Len volunteered to

make reservations, and using the Internet and a Michelin guide, he quickly

nailed down our accommodations everywhere except at Milltown.

Instead, he got hotel rooms in Lehinch, which was about 8 miles further

to the north.

I

handled the bike reservations using the Raleigh website in Ireland.

I didn’t hear back from my inquiry for about a week, and then I was

referred to a particular bike shop in Cork.

Subsequently, I exchanged email messages with an Aidan Quindlan in that

shop, and made reservations for 2 bikes to be returned in Galway.

As

you can see from the shading on the relief map above, there are many hills and

mountains in Ireland. It’s not as

if they are like the Alps, but they were a concern for me, since I almost always

bike in the flatlands of coastal New Jersey.

I was also intimidated by reading the book “Round Ireland in Low

Gear” by Eric Newby. Mostly I

found this book quite boring, as it had so much detail related to the arcane and

convoluted history of Ireland, but the thing that most impressed me about his

biking was the constant need to climb long hills to wherever he was going.

In

order to understand the hills on the planned itinerary, I needed detailed maps

with topological information. Fortunately,

such maps are available for all of Ireland from the Ordnance Survey Mapping

Agency in the UK. These are

wonderful maps, as I had learned in my previous bike trip to East Anglia.

In fact, on the back cover of Bill Bryson’s immensely popular book,

“Notes from a Small Island”, is reprinted a paragraph from the text listing

the three greatest things about England. I

forget what two of them were, but the third was the existence of the Ordnance

Survey maps. These maps are so detailed that they not only show elevation

gradients, but even individual houses, phone booths, and ancient artifacts,

among other things.

The

problem is that it is hard to find these maps in the United States.

I had found a small store on the seventh floor of a building in Manhattan

that carried all of the maps for England, but I couldn’t find any place that

stocked the maps for Ireland. Previously

I had even tried to order maps from a national service dealer on the Internet,

but I never even heard back about my order.

I also visited a map store in Washington, D.C. that was listed on the

Ordnance Survey web site as stocking their maps, but their collection contained

only the larger scale “Holiday” maps for Ireland.

I

had temporarily forgotten about my need for these Ordnance Survey maps when in

February I was walking down Charing Cross Lane in London passing by one of my

favorite bookstores, Foyle’s. It

suddenly popped into my head – of course, they would have all of these maps.

The English believe in maps. Not

only did Foyle’s have all of the Ireland maps, but I later discovered a map

store near Covent Garden that had three large floors of maps even for countries

that I that didn’t know existed. Now

this was a map store! In that store

Ireland was so mundane that it rated only a dusty corner of the basement.

But they also carried all of the Irish Ordnance Survey maps.

Faced

with the bonanza of all of these maps, I had a difficult decision to make –

one that I have since had occasion to rethink.

The problem is that it takes 89 of these maps to cover Ireland.

Each map contains only about a 20-mile square, so it would take more than

a dozen to encompass my proposed itinerary.

Each map cost about $10, and more importantly would take valuable space

and weight in my panniers. In the

end I decided to buy five maps that covered about 75% of the trip.

In order to cover the other 25% I would have had to buy about six more

maps, each covering only some small part of the remaining itinerary.

It was a compromise, and my past experience had been that whenever I got

lost, it was in one of those little areas where I didn’t have the detailed

map. Nonetheless, I didn’t buy

them all, and as I will relate later, not having those remaining maps made an

impact on my subsequent bike trip.

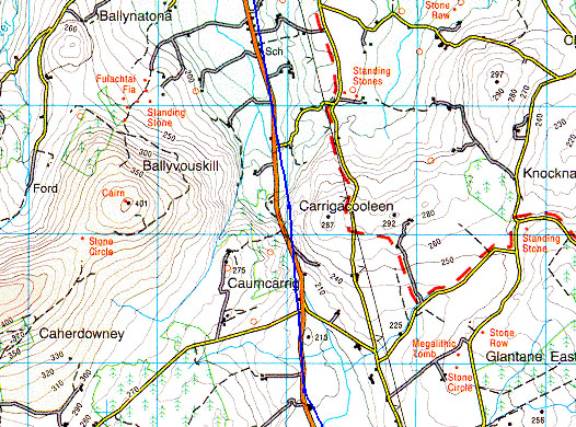

Shown

above is an example portion from one of the maps I bought.

The blue line shows my proposed route through this section.

The scale is such that each square on this map is one kilometer (about

0.6 miles). At a normal riding

speed on a bike I would cross one of these squares in about three to four

minutes. Notice the information

about the positions of stone circles, megalithic tombs, and standing stones.

Most importantly, however, notice the elevation contours, which are lines

of constant elevation spaced at 10-meter intervals.

Whenever I would cross one of these contour lines, I would be going up or

down by about 33 feet. The worst

thing would be to bike perpendicular to a lot of those lines where they are

close together. You can see that

this section of County Cork, between Cork City and Killarney, is relatively

mountainous, and that the proposed route threads delicately among the hills.

I

did some comparison with hills that were near my home in New Jersey.

I knew how relatively hard they were to bike, but I didn’t know their

gradients, as I did for the hills that I had never seen in Ireland.

Then I was able to get the Delorme software of topological maps of the

United States, and on my computer I could trace out routes on streets where I

live and see their changing elevation. I

found that a guideline for my experience was that I could continuously cross

three of those ten-meter gradients within a one-kilometer square. More would be a problem.

As it turned out subsequently, more it was.

In

choosing the route I tried to pay attention to the gradients so as to avoid

hills. However, as I later

discovered, I didn’t pay enough attention.

You can see in this example that the gradients are very close together

and the question is how many and how often the route crosses these elevation

lines. Without a magnifying glass

and a lot of study, it’s hard to tell. In

the actuality I found that it was more reliable to look at the specific

elevations noted on the map (for example, the “213” meter height near the

bottom of the blue line) and to see how much that changed by the next such

point. But I didn’t realize that

until I was on my bike puffing my way up unexpectedly difficult hills.

There

was another difficulty in interpretation of the Ordnance Survey Maps.

Which roads were friendly to bikes, and which not?

I had no idea. In this

example the yellow roads are “secondary roads”, and I supposed that these

were narrow roads without much traffic. The

red road, however, was a “main” road. I

assumed that here we would find considerable traffic, and perhaps there

wouldn’t be a shoulder for bikes. Maybe

we had to avoid such roads. It

isn’t shown here, but there also were dotted-green and green roads, and I

supposed that these highways absolutely had to be avoided.

I wish that they made maps specifically for bikers with traffic, width,

and safety information, but I have never seen such a thing.

My

navigation in my two previous European trips had left something to be desired.

On a number of occasions I had gotten lost.

Getting lost in a car is no big deal – you just keep driving until you

discover where you are. But on a

bike it had cost me ten miles of riding a couple of times, and that is no small

thing. On both trips I had taken my handheld GPS, but it had been

pretty worthless for several reasons. First,

I hadn’t learned to use it well – specifically to set up the custom display

in a useful format. Second, I did

not have a bike mount for the GPS, so I carried it inconveniently in my fanny

pack. Moreover, since the thing

eats batteries, I only turned it on every now and then.

Finally, although I had programmed the coordinates of destination cities,

the GPS knew nothing of the route between the cities. Overall, it had been pretty worthless.

For

Ireland I intended to make the GPS useful.

This wasn’t so much a necessity, given good maps, but it was mostly for

techie fun. I discovered that

Magellan had just marketed a bike mount for the model 315 that I had, and so I

ordered that. At the same time I

ordered a computer connector and mapping software (by Fugawi) that would allow

me to upload and download information between my PC and the GPS.

Then I experimented with the GPS on my bike in New Jersey and, after

having had the thing for two years, I finally learned how to use it well.

In fact, it did a lot of things that I had not realized, and one

especially important feature was that it could display Irish grid coordinates.

Those are the coordinates in Ireland given on the Ordnance Survey Maps

instead of latitude and longitude, and which measure directly kilometers of

distance. So using the GPS

coordinates and my maps, for example, I could walk directly up to one of those

marked standing stones and be within feet of it just using the GPS display

information.

The

Fugawi software allowed me to scan the Ordnance Survey maps, calibrate the

computer with three coordinate positions on each map, and then to draw routes

and mark landmarks that could be uploaded to the GPS. So, for example, the blue line in the picture above was drawn

on my computer screen and uploaded into the GPS.

When I got to Ireland the GPS would show me exactly where I was in

relation to that designated path. How

could I go wrong?

Later

I made a very small discovery that made a great deal of difference in my

attitude towards the GPS. The fact

that the thing ate batteries really got into my mind, and I was always afraid to

leave it on. Typically, it would

exhaust its two AA batteries in only a few hours of cycling.

I calculated that I would need several dozen batteries for the trip in

Ireland. I had been watching the

battery websites to see if anyone had begun making lithium AA batteries, which

would last a lot longer. One day I saw that Energizer was starting to market lithium

AA batteries that lasted up to five times as long as alkaline batteries, and

weighed only half as much. Just

what I needed! Moreover, these same

lithium batteries could be used for my digital camera, an Olympus C-3000 that

also loved to eat batteries.

I

bought some lithium cells and used the GPS on my bike in New Jersey for several

weeks. I clocked over a hundred

miles and the GPS said the batteries were still fully charged.

What a difference! Now I could forget about the battery drain and leave the GPS

on constantly. Not only would it

show me exactly where I was and the route to be taken, but it would also give me

speed, altitude, odometer, compass, time, and even times for sunrise and sunset

and phase of the moon if you cared. Neat

gadget! The odometer functions were

especially important to me psychologically, because with a rental bike I would

not have my usual bike odometer and I would “lose” the miles that I had

biked. I have a compulsion to bike

so many miles a year, and I have this compelling need to know where I stand

relative to that goal.

Each

year previously I had learned something about how not to pack.

On the one hand, I had to be prepared for every kind of weather and

contingency – rain, heat, cold, repairs, medicines, etc.

On the other hand, every pound carried was a pound that had to be lugged

up hills. In Holland that hadn’t been a problem, since in a flat

country weight wasn’t so important as was the relative wind resistance.

Volume was also a consideration. My

own panniers held 2400 cubic inches of content, and I used that as a guideline.

Roughly, that would be a small suitcase – something like 12 inches by

20 inches by 10 inches.

By

email Len and I discussed the packing situation. We weren’t sure that whatever panniers we had would fit the

rental bikes, and so we decided to rent panniers to go with the bikes.

In planning we used the 2400 cubic inch guideline, and it was only a day

or so before we left that I discovered from the rental website in Ireland that

the rented panniers would hold a monstrous 3600 cubic inches.

That would be, of course, only so much more weight, so it was pretty

irrelevant information at that time.

In

retrospect, as in previous years, I took too much. My pack weighed in at about 25 pounds. I think I could have cut it back by a third.

I took two biking outfits, rain gear, long biking pants, one pair of

“evening” pants and several shirts, a sweater, sweatshirt, toiletries,

guidebook, reading book, maps, tools, underwear, socks, and miscellaneous

things. In addition to the panniers

to be rented Len and I both bought handlebar bags to mount on the rented bikes.

These handlebar bags would also serve as map-holders, and would

conveniently carry guidebooks and tools at the ready.

We took fanny packs to keep valuables – wallet, passport, and camera

– on our persons at all times, whether or not we were on the bikes.

There was always the issue of whether we would leave the panniers on the

bikes when they were parked and locked. In

fact, it was so inconvenient to remove and restore the panniers that there

wasn’t much choice. The only

option was not to have anything very valuable stored in the panniers.

Another

issue was whether to carry or wash. In

the cool rainy climate of Ireland things wouldn’t dry very well overnight.

My biggest problem was socks. They

used up a lot of space – particularly the white wool biking socks.

Len made a very useful suggestion of getting thin cotton socks, which

would not only take less space but would dry much more quickly, and this turned

out very well. I took four pairs,

and did several overnight washings. I

also had to count on overnight washings of my primary biking outfits.

In

England the weather had been very hot for my trip, and I had needlessly carried

warm clothes and raingear. Then in

Holland I had been unprepared for the cold, and had worn raingear every day.

This time I decided not to take any warm weather clothes, given the cool

temperatures typical of July in Ireland (usually in the high 50s).

Raingear was an obvious necessity. Every

day I would check the forecast on the Internet for Cork.

Every day it was the same – showers.

Occasionally the forecast would be different, and it would say

“rain.”

One

of the controversial items was a guidebook for Ireland.

The problem is that these things are heavy.

I had several that were good – the Lonely Planet guide and the Rough

guide. They’re both heavy.

In both England and Holland I had decided that guidebooks weren’t worth

the weight, and I had copied only the relevant pages and had carried them loose.

Then in trying to use these loose pages I could never find what I wanted.

So for Ireland I decided to take the Rough guidebook, while Len took the

Lonely Planet guidebook. In

retrospect neither taking the book or not taking it seems best.

The problem is that in the 700 pages or so of the guidebook there are

only about 25 that are relevant to the trip.

The rest are a heavy waste.

Another

small, vexing issue was how to carry my gear before and after putting it in the

bike panniers. I obviously

couldn’t take a suitcase, since what would I do with it? The ideal solution would have been a duffle bag made of thin

silk or some such material that would weigh almost nothing and take almost no

space in my panniers. It wouldn’t

have to be durable since it only had to last a couple of days before and after

the biking portion of the trip. After

several visits to different travel and luggage stores I gave up trying to find

such a thing. I guess there’s no

profit in cheap, light throwaway bags. Instead

I decided to use a heavier duffle bag that had been a gift at some conference

years before. Not only was it

heavier than I’d have liked, but it didn’t fold very well.

I figured I could fold it just well enough to use bungie cords to attach

it on top of the back rack of the bike. If

that didn’t work, I was prepared to throw it away in Cork and buy a new bag in

Galway.

There

was one portion of our email about packing that really struck me as funny.

Len wrote that he was considering taking a telescoping pointer to fend

off dogs that might chase us. I had

this fantasy where Len would extend the pointer and parry at the dog like some

kind of fencer. I also imagined

that this would piss off the dog no end, and that he might decide to take it out

on me. As it turned out, Len

didn’t take the pointer, but he did take pepper spray.

He never used it, though.

So

much for the preparations. They

took many months of email discussion and served as a nice way of dreaming and

learning about the forthcoming trip. By

and large, the preparations and logistics worked well, but as always I did have

a few lessons learned. Principally,

I needed to have had all of the relevant maps and to have studied them more

closely. Also, and once again, I

took too many things. The

sweatshirt, for example, was a bad idea. It

just got soaked with perspiration every day.

And I never wore the long-legged bike pants, which were redundant with my

rain pants, which in turn were a cheap design that was unnecessarily heavy.